“As we understand it, the church sets up standards which do not make it easy for the run-of-mine Canadians and the foreign-born population to find common ground. There is a conscientious objector side of it which, at a time when Canada’s finest are fighting and dying, makes for hard feelings. There is the German language side of it, which, at a time when our men are fighting and dying to combat the German menace, offers little chance for cooperation.”

- Abbotsford Sumas Matsqui News, 22 Dec. 1943

Yarrow Pioneers, 1928. Mennonite Historical Society of BC [125-5-3-2011.016.026]

Mennonites are a religious group that descended from 16th century Anabaptists in Europe. Russian Mennonites first came to Canada in 1823. Often viewed as undesirable by the non-Mennonite Canadian community, Mennonites faced discrimination, and immigration was banned in 1919, due in part to anti-German sentiments after World War I. In 1921 the ban was lifted, and a large wave of Russian Mennonites arrived in Western Canada between 1923 and 1929 under the arrangement that they would live and work as farmers. Many Mennonites were resistant to assimilation into Canadian society, and on the other hand, were seen by many Canadians as unable to assimilate.

Conscientious Objection

The early years of World War II brought increased tension for the relationship between Mennonites and their non-Mennonite neighbors in Abbotsford and Yarrow. Mennonites were accused of not participating in the war effort; they were eligible for the status of conscientious objection, which the community viewed as not fulfilling their responsibility as citizens. Another source of tension was the sale of farmland to Mennonites while others were serving at war. In a letter to the editor of the Chilliwack Progress, W.A. Baird writes, “I am fearful of the day when our boys return and find a lot of the best land in our valley in the hands of people who were not willing to defend it.” The accusations against Mennonites of not serving at war have been said to be an exaggeration of the truth, as more Mennonites than was commonly thought served in the military; however, the negative perception of the group remained.

For more information on perceptions of Mennonite participation in World War II, visit “The Mennonite Menace: Real or Imagined?” by Kelsey Siemens.

Separatism

“There appears to have been an almost instinctive understanding that ‘Germanness’ was basic to Mennonite survival in an alien culture.”

- John B. Toews in Village of Unsettled Yearnings: Yarrow, British Columbia: Mennonite Promise by Leonard Neufeldt

A major criticism of Mennonites was their isolation from society. Mixing with English-speaking citizens was typically avoided, and marriage to non-Mennonites was discouraged. A main instrument of separatism was the German language. Children were sent to German School on Saturdays where they were taught to read and write in German, and church services and classes at Elim Bible School in Yarrow were in German. The language was a central aspect of Mennonite identity; many felt that if the language was lost, Mennonite culture and ideals would also be lost. For this reason, many stressed the importance of speaking German and avoided speaking English.

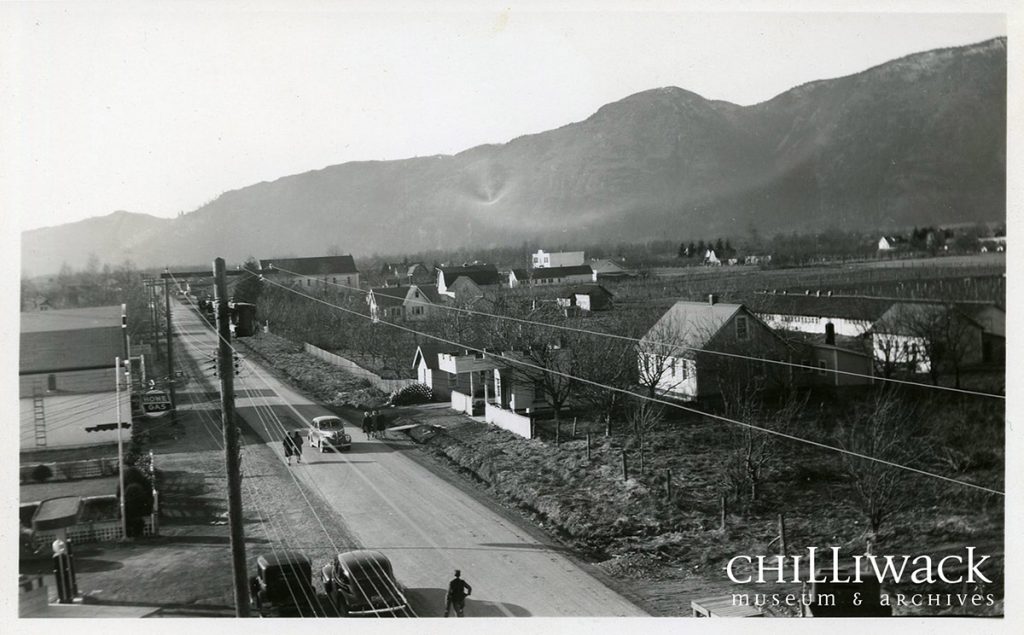

Yarrow, 1940s, M.B. Church and Elim Bible School can be seen in the background (right). Photograph courtesy of the Chilliwack Museum and Archives [2010.031.004]

The German language was perceived negatively by the non-Mennonite community. Newspapers feature complaints from the English-speaking community over the use of German, largely due to the pressures of war. Mennonites were accused of speaking the “Hitler language” and teaching their children to do the same, and it caused many to view Mennonites as less than Canadian citizens.